by Dr. Jim Webber & Dr. Mark Little

In July 2002, BEA, IBM, and Microsoft released a trio of specifications designed to support business transactions over Web services. These specifications - BPEL4WS, WS-Transaction, and WS-Coordination - together form the bedrock for reliably choreographing Web services-based applications, providing business process management, transactional integrity, and generic coordination facilities respectively.

This article introduces the underlying concepts of Web Services Coordination, and shows how a generic coordination framework can be used to provide the foundations for higher-level business processes. In future articles, we will demonstrate how coordination allows us to move up the Web services stack to encompass WS-Transaction and on to BPEL4WS.

Coordination

In general terms, coordination is the act of one entity (known as the

coordinator) disseminating information to a number of participants for

some domain-specific reason. This reason could be in order to reach

consensus on a decision like a distributed transaction protocol, or

simply to guarantee that all participants obtain a specific message, as

occurs in a reliable multicast environment. When parties are being

coordinated, information known as the coordination context is

propagated to tie together operations that are logically part of the

same coordinated work or activity. This context information may flow

with normal application messages, or may be an explicit part of a

message exchange and is specific to the type of coordination being

performed. For example, a security coordination service will propagate

differently formed contexts than a transaction coordinator.

Despite the fact that there are many types of distributed applications that require coordination, it will be no surprise to learn that each domain typically uses a different coordination protocol. In transactions, for example, OASIS Business Transactions Protocol and Object Management Group's Object Transaction Service are solutions to specific problem domains that are not applicable to others since they are based on different architectural styles.

Given the domain-specific nature of these protocols (i.e., loosely coupled transactional Web services and tightly coupled transactional CORBA objects) there is no way to provide a universal solution without jeopardizing efficiency and scalability in each individual domain; and not everyone wants to (or can afford to) have a full-blown transaction processing system in order to do coordination. However, both of these protocols have the underlying requirement for propagating contextual information to participants, and therefore it would make some sense if that mechanism could be made generic, and thus reused. On closer examination, we find that even solely within the Web services domain we encounter situations where coordination is a requirement of several different types of problem domain, such as workflow management and transaction processing, but where the overall models are very different yet that same requirement for coordination is still present.

WS-Coordination

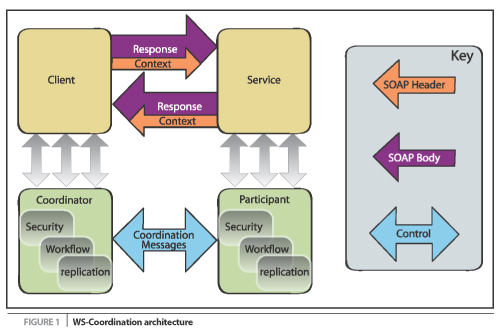

The fundamental idea underpinning WS-Coordination is that there is

indeed a generic need for propagating context information in a Web

services environment, which is a shared requirement irrespective of the

applications being executed. The WS-Coordination specification defines

a framework that allows different coordination protocols to be plugged

in to coordinate work between clients, services, and participants (see

Figure 1). The WS-Coordination specification talks in terms of

activities, which are distributed units of work involving one or more

parties (which may be services, components, or even objects). At this

level, an activity is minimally specified and is simply created, made

to run, and then completed.

In Figure 1, we suggest that the framework is useful for propagating

security, workflow, or replication contexts, though this is by no means

an exhaustive list. Nonetheless, whatever coordination protocol is

used, and in whatever domain it is deployed, the same generic

requirements are present:

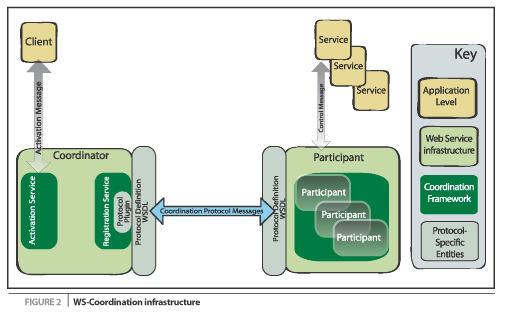

The first three points are directly the concern of

WS-Coordination, while the fourth is the responsibility of a

third-party entity, usually the client application that controls the

application as a whole. These four roles and their interrelationships

are shown in Figure 2. Activation

Registration When a participant is registered with a

coordinator through the registration service, it receives messages that

the coordinator sends (for example, "prepare to complete" and

"complete" messages if a two-phase protocol is used); where the

coordinator's protocol supports it, participants can also send messages

back to the coordinator.

Completion

Context

While the first three points are common sense, the fourth is

somewhat more interesting. Since WS-Coordination is generic, it is of

very little use to applications without augmentation, and this is

reflected in the part of the WS-Coordination XML schema for contexts.

In Listing 3, the schema states that a context consists of a URI that

uniquely identifies the type of coordination that is required

(xs:anyURI), an endpoint where participants to be coordinated can be

registered (wsu:PortReferenceType), and an extensibility element

designed to carry specific coordination protocol context payload

(xs:any), which can carry arbitrary XML payload. (Note: This type also

inherits some useful features from its parent in the form of a

time-to-live value and an identifier.) Coordinating Business Processes on the Web

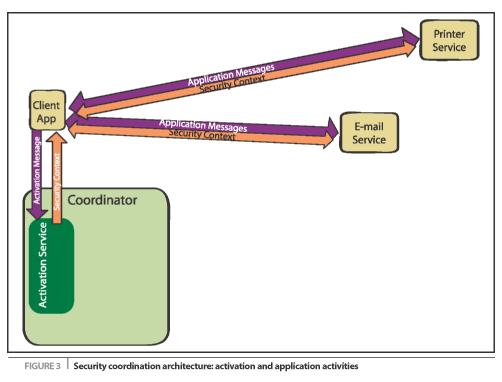

Here we see the initial stages of the application. The client

application locates an activation service and sends it a message asking

for the creation of a security coordinator and a corresponding security

context, passing appropriate user credentials as part of the activation

process as shown in Listing 4. Assuming that a security

coordination service has been registered with the coordination

framework, a coordinator is created (and exposed as a registration

service) and a context like that in Listing 4 is duly returned to the

client application as part of the CreateCoordinationContextResponse

message. The client application interacts with its component

Web services sending and receiving messages as normal, with the

exception that it embeds the coordination context (which carries the

security information) in a SOAP header block in its messages to provide

authenticity credentials for those services that are invoked.

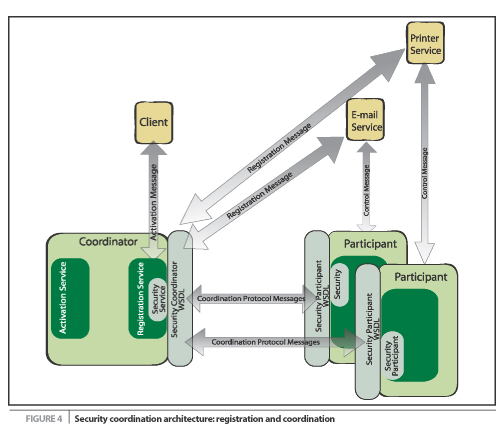

Let's assume that a service understands the protocol messages

associated with our simple centralized sign-on service, and furthermore

hasn't registered a participant previously. Once the service receives a

SOAP message containing a security context header (see Listing 5), it

registers a participant with the coordinator using the details provided

in the context (via the WS-Coordination registration service URI, for

example). This registration operation occurs every time a service

receives a particular context for the first time, which ensures that

all services register participants within the activity. When

the client decides to terminate its session and log out of the services

it has been using, it sends a completion message to the coordinator; in

turn, the coordinator informs each registered participant to revoke the

privileges for the client application, preventing it from using their

corresponding services. Any subsequent calls by the client to that

service with the same context will result in the service being unable

to register a participant since the context details will no longer

resolve to a live coordinator to register with (see Figure 4).

At some point, the client application finishes its work and must run

the completion protocol to force its own system-wide logoff. To do

this, it sends a security protocol logoff message to the security

coordinator. This message is entirely out-of-scope of WS-Coordination

and is instead defined by the specification of our security protocol

which plugs in to the WS-Coordination framework. The completion message

is shown in Listing 6. In response to receiving this message,

the security coordinator informs each of its registered participants to

terminate the user's current session. To do this, it sends each of the

participants a signOut message to which they respond with a signedOut

message, confirming that the user is no longer authenticated with that

particular participant's associated service. The pertinent parts of the

signOut and signedOut messages are shown in Listing 7. Once a

signedOut message has been received from each of the enrolled

participants, it can report back to the client application that its

session has been ended. The final message in our WS-Coordination

protocol is the loggedOut response message from the security

coordination to the client (see Listing 8).

Advanced Usage Scenarios

Interposition is a way of creating a hierarchy of coordinators, each of

which looks like a simple participant to coordinators higher up the

coordination tree, yet acts just like a normal coordinator for

participants lower down the tree. Coordinators become registered within

this hierarchy if the client application sends a CreateCoordination

Context message to an activation service along with a valid context.

When the receiving activation service creates the new context (and

associated coordinator/registration service), it uses the original

context to determine the endpoint of its superior coordinator (a.k.a.

registration service) and enrolls the new coordinator with it.

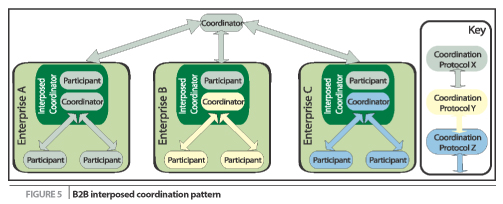

In Figure 5 we see a typical interposed coordinator arrangement

spanning three different enterprises using two different coordination

protocols. This arrangement is arrived at through a client application

creating a top-level context and then invoking Web services within the

bounds of its partner enterprises. In the noninterposed case, upon

first receipt of a context embedded in a SOAP header a service

registers a participant with the coordinator identified by the context.

However, in this situation, for reasons such as security or

trustworthiness, the service enrolls its own coordinator by sending an

activation message loaded with the top-level context to a local

activation service, and then registers with the newly created local

coordinator. (Note: By using ts own coordinator, the service

or domain in which it resides only exposes the coordinator to the

superior and not the individual participants. This may be useful in

restricting the amount of information that can flow out of the domain

and hence be available to potentially upotentially unsecure or

untrusted individuals/services.)

Having received a context with an activation message, the newly created

coordinator duly registers itself with the registration service that

the context advertises. The top-level coordinator is unaware of this

arrangement since it sees the interposed coordinator as a participant,

while the local participants are coordinated by their own local

coordinator, which confers the following advantages:

In Figure 5 Enterprise A uses the same coordination protocol as

the top-level coordinator. In this case, Enterprise A's coordinator

coordinates local participants according to the same protocol as the

top-level. However, since only the outcome of the local coordination

needs to be sent over the Internet to the top-level coordinator, and

not the more abundant coordination protocol messages, this approach is

performance-optimized, compared to registering Enterprise A's

participants directly with the top-level coordinator. For

Enterprise B and Enterprise C, the same performance benefit exists,

although the real focus of coordinating these participants is the fact

that they are coordinated with different protocols that suit the

particular enterprise's needs and not necessarily the same coordination

protocol used at the top level. Since the local coordinator for each

enterprise is effectively "bilingual" in the coordination protocols

they understand (knowing both the participant aspects of the top-level

coordination protocol and the coordinator aspects of their own internal

coordination protocols), different coordination domains can easily be

bridged without adding complexity to the overall architecture.

Summary Though WS-Coordination is

generically useful, at the time of this writing only one protocol that

leverages WS-Coordination has been made public: WS-Transaction We'll

look at this protocol in our next article.

Author Bio

Dr. Jim Webber is an architect and Web services fanatic at

Arjuna Technologies where he works on Web services transactioning and

Grid computing technology. Prior to joining Arjuna Technologies, he was

the lead developer with Hewlett-Packard working on their BTP-based Web

Services Transactions product - the industry's first Web Services

Transaction solution. An active speaker and Web Services proponent, Jim

is the coauthor of "Developing Enterprise Web Services."

Listing 1: Activation Service WSDL Interfaces

Where is Sun Microsystems?

It seems great that BEA, Microsoft and IBM are all making millions $$$

on WS-coordination effort to make their platform, software compatible.

But what about Sun? What kind of role it plays? After all, Java is the

thread for all of these efforts. Sun should play more active role in

Web Server and Web Services market by jumping onto the bandwaggon!

I think Microsoft might have a few things to say about "Java is the

thread ..." since their offerings won't be Java based ;-) I don't have

any insights I can share as to what Sun is doing in this area, but

there's obviously a lot going on in the Java space, what with J2EE and

JCP, and there has been a lot of effort over the last year on Web

Services in J2EE. So, maybe it's just a matter of timing?

We tend to equate Java = Sun. Today, my believe is not so. IBM &

others are very deep into Java as well. Moreover, WS is not about Java.

WS is independent of tools.

Hi, I working in my Tesis, and need information of analyst and design of webservices.

The WS-Coordination framework exposes an Activation Service that

supports the creation of coordinators for specific protocols and their

associated contexts. The process of invoking an activation service is

done asynchronously, so the specification defines both the interface of

the activation service itself, and that of the invoking service, so

that the activation service can call back to deliver the results of the

activation - namely a context that identifies the protocol type and

coordinator location. These interfaces are presented in Listing 1,

where the activation service has a one-way operation that expects to

receive a CreateCoordinationContext message, and correspondingly the

service that sent the CreateCoordinationContext message expects to be

called back with a CreateCoordination ContextResponse message, or

informed of a problem via an Error message.

Once a coordinator has been

instantiated and a corresponding context created by the activation

service, a Registration Service is created and exposed. This service

allows participants to register to receive protocol messages associated

with a particular coordinator. Like the activation service, the

registration service assumes asynchronous communication and so

specifies WSDL for both registration service and registration requester

(see Listing 2).

The role of terminator is

generally played by the client application, which at an appropriate

point will ask the coordinator to perform its particular coordination

function with any registered participants - to drive the protocol

through to its completion. On completion, the client application may be

informed of an outcome for the activity, which may vary from simple

succeeded/ failed notification through to complex structured data

detailing the activity's status.

The context is critical to

coordination since it contains the information necessary for services

to participate in the protocol. It provides the glue to bind all of the

application's constituent Web services together into a single

coordinated application whole. Since WS-Coordination is a generic

coordination framework, contexts have to be tailored to meet the needs

of specific coordination protocols that are plugged into the framework.

The format of a WS-Coordination context is specifically designed to be

third-party extensible and its contents are as follows:

To show WS-Coordination in action, we'll consider a centralized sign-on

service that enables a client application to authenticate once, and

then use given credentials to access a number of Web services, and to

de-authenticate from the system with a single operation irrespective of

the number of Web services that are invoked. (Note: It's

important to note that although the coordination strategy outlined here

is reasonable enough, the patter as a whole isn't industrial strength

since we avoid clouding the coordination issues by drawing on other

useful technologies such as XML encryption and XML signature, which a

truly trustworthy implementation would utilize. You should remember

while following this example through that a real implementation would

draw heavily on security standards like XML-encryption to provide the

necessary privacy and XML digital signatures to provide authenticity.)

The initial coordination pattern for this scenario is captured in

Figure 3.

In our security coordination example, the overall architecture is

relatively static and known in advance of the coordination. However, it

may be that in a business-to-business scenario we would like the

ability to coordinate arbitrary groups of Web services as part of a

single, logical, coordinated application. WS-Coordination supports this

through a scheme known as interposition.

WS-Coordination looks set to become the adopted standard for activity

coordination on the Web. Out of the box, WS-Coordination provides only

activity and registration services, and is extended through protocol

plug-ins that provide domain-specific coordination facilities. In

addition to its generic nature, the WS-Coordination model also scales

efficiently via interposed coordination, which allows arbitrary

collections of Web services to coordinate their operation in a

straightforward and scalable manner.

Dr. Mark Little is chief architect, transactions, for Arjuna

Technologies Limited, a spin-off from Hewlett-Packard that develops

transaction technologies for J2EE and Web services. Previously, Mark

was a distinguished engineer and architect at HP Middleware, where he

led the transactions teams. He is a member of the expert group for JSR

95, and JSR 117, is the specification lead for JSR 156, and is active

on the OTS Revision Task Force and the OASIS Business Transactions

Protocol specification. Mark is the coauthor of J2EE 1.4 Bible and Java

Transactions for Architects.

Jim.Webber@arjuna.com

message="wscoor:CreateCoordinationContext"/>

name="CreateCoordinationContextResponse">

message="wscoor:CreateCoordinationContextResponse"/>

Listing 2: Registration Service WSDL Interface

Listing 3: WS-Coordination Context Schema Fragment

abstract="false">

type="xs:anyURI" />

type="wsu:PortReferenceType" />

minOccurs="0" maxOccurs="unbounded" />

Listing 4: Security Coordination Activation Message

xmlns:soap="http://www.w3.org/2002/06/soap-envelope">

xmlns="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/ws/2002/08/wscoor"

xmlns:wsu="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/ws/2002/07/utility"

xmlns:security="http://security.example.org/authentication">

http://activation.example.org

a.n@other.com

foobar

http://workstation.example.org/station101

http://security.example.org/single-logon

Listing 5: A Security Context

xmlns:soap="http://www.w3.org/2002/06/soap-envelope">

xmlns="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/ws/2002/08/wscoor"

xmlns:wsu="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/ws/2002/07/utility"

xmlns:security="http://security.example.org/authentication">

http://workstation.example.org/station101

http://security.example.org/single-logon

http://security.example.org/registration

1234-5678-9ABC-DEF0

Listing 6 Security Protocol Completion Request Message

xmlns:soap="http://www.w3.org/2002/06/soap-envelope"

xmlns:wscoor="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/ws/2002/08/wscoor"

xmlns:wsu="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/ws/2002/07/utility"

xmlns:sec="http://security.example.org/authentication"

xmlns:comp="http://security.example.org/authentication/

completion">

http://workstation.example.org/station101

a.n@other.com

foobar

Listing 7 signOut and signedOut Message Contents

http://security.example.org/logout-service

a.n@other.com

http://printer.example.org/logout-service

a.n@other.com

Listing 8 The loggedOut Message indicates session termination

xmlns:soap="http://www.w3.org/2002/06/soap-envelope"

xmlns:wscoor="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/ws/2002/08/wscoor"

xmlns:wsu="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/ws/2002/07/utility"

xmlns:sec="http://security.example.org/authentication"

xmlns:comp="http://security.example.org/authentication/

completion">

http://security.example.org/authentication

a.n@other.com

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Reader Feedback

Posted by Donald Hsu on May 6 @ 06:13 AM

Where is Sun?

Posted by Mark Little on May 7 @ 04:54 AM

Mark.

Where is Sun?

Posted by Sei ES on Jun 9 @ 09:28 PM

Help

Posted by peter on Apr 5 @ 12:19 PM

please help me!!

thank you.